As a child, one of the lessons I received on living as a Buddhist was on the treatment of Buddhist texts. These were the recorded words of the Buddha, or the comments of great sages; in other words, srarira, physical relics of the Buddha. As the Lotus Sutra reads,

O Bhaiṣajyarāja! Wherever this sutra is taught, read, recited, copied, or wherever it is to be found, one should build a seven-jeweled stupa of great height and width and richly ornamented. There is no need to put a relic inside. Why is this? Because the Tathāgata is already in it. This stupa should be respected, honored, praised and rendered homage with offerings of all kinds of flowers, perfumes, necklaces, canopies, flags, banners, music, and songs. If there is anyone able to see this stupa and to pay it homage and honor it, know that such a one is nearing highest, complete enlightenment.

Lotus Sutra, Kubo Tsugunari and Yuyama Akira, Trs., 2007, p. 161.

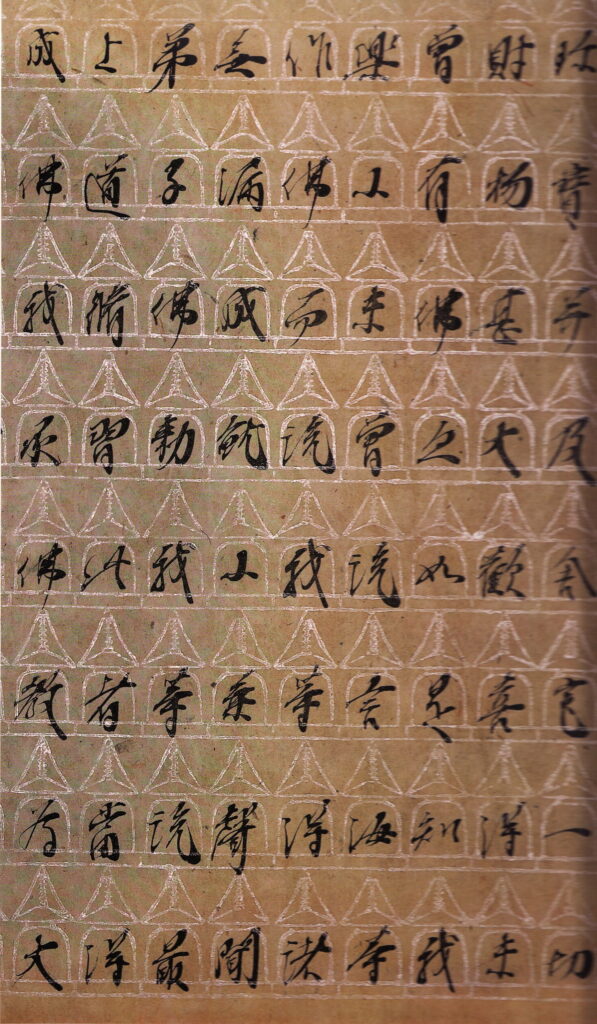

In the past, the Buddha’s teachings were transmitted orally, and only centuries later, committed to writing, assiduously copied by hand. Still centuries further on, Buddhists in China printed copies of texts using woodblock technology. Eventually, movable type technology presented a further innovation, and now, modern means of reproduction – facsimiles, copiers, and now, ubiquitous digital copies are possible. Access to the Dharma has never been so easy.

They say, “time is money.” The sentiment succinctly conveys how we value things based on the time and effort required to bring that thing about. For better and worse, we apply this standard all the time – we naturally value things that demand effort – a diamond compared to a shard of glass; a PhD compared to the passing sense impression of a blue sky.

At one time, the teachings flowed directly from bodhi embodied by the Buddha. What incalculable value! An opportunity to directly see how bodhi dwells in the world, to witness its conduct as a human being, and to ask and receive instructions on how we can attain bodhi ourselves. But the nirmanakaya Buddha is himself subject to impermanence and he taught for a brief period of some 40 years. The immediately following generation received recollections of the direct impressions of those who personally knew the Buddha, but these people, too, passed within decades. As the years, decades, and centuries rolled on, only the impressions of impressions, generations removed, remained, fading echoes of the Buddha’s voice.

In my generation, the last to come of age before the deluge of digitally recorded information, these words were recorded in finely bound books, albeit mass produced in factories. But they had tangible value, not only in their physical form, but in their sale price. We weren’t rich, and so to spend our limited resources on these books meant the contents were special to us – more important than a new trinket or ephemeral experience. In my grandmother I had the example of a person for whom these books were even more valuable, and who was vastly closer to premodern Buddhist culture. “We do not put sutra books on the floor!” In her example was a person who deeply lived the instructions to Bhaisajyaraja.

If the entire Tripitaka can be held on a micro chip smaller than one’s thumbnail with ample space to also hold the further contents of good sized library, and which can be copied in a matter of seconds, transmitted anywhere on the planet with an internet connection, does this affect our visceral valuation of the Teachings? I believe it does.

The circumstances we live in more acutely demand that we make the requisite effort to cultivate right views on the Buddha’s teachings. As we lose the sense of value based on time and effort, we are required to directly weigh the meaning of the teachings and appreciate their value. We can do this by being mindful that the pixels on the screen are srarira, requiring our appropriate disposition. We lament the vacuous nature of our digital activities, but here we have an opportunity to turn our experience with digital information into meritorious activity.

How can we practice this? We can take our cue from other forms of practice that incorporate daily activities, such as meal prayers. In the Tendai tradition, we have practices that turn meals into meritorious activity by framing them within certain reflections. Similarly, as we open a digital text we can reflect that we are viewing the Buddha’s body and when reading it, hearing the Buddha’s voice, and when reflecting on it, we are interacting with the Buddha’s mind.

Leave a Reply